How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

Scholars are divided on whether Elizabeth Barrett Browning was writing about Robert Browning or about cricket but her words came to me as I pondered my experience as a spectator in the crowd at the England V Pakistan World Cup match last Monday at Trent Bridge. (An intelligent, passionate poet, I think Elizabeth might have enjoyed cricket – although would have struggled with eight hours in the opium-free stand.)

Anyway. Her words dropped into my brain as I sat quietly watching the match while the Pakistani supporters leapt around me with ineluctable vigour. While there is no doubting their love of the game and their team, it became apparent that much of their more outrageous dancing and chanting came at the same time as the appearance of a TV camera.

And it wasn’t just the Pakistan supporters. The England-supporting schoolkids in front of us were frequently briefed by the cameraman to perform on cue. The camera didn’t just happen to capture some 10 year olds playing air guitar along to the terrible guitarist who was playing live during breaks in play, it captured them doing it because the cameraman had told – and shown – them what to do and when to do it, each of them performing on cue as he pointed at them one by one. The camera then moved away and they settled down to resume watching quietly and eating sweets.

Beyond the choreographed enjoyment, the simple presence of the camera changed the crowd dynamic. When it pointed at anyone, they leapt up to cheer and shout and wave. When it pointed at the Pakistan supporters, they launched into chants and dances.

We’re sophisticated enough to know now that just because something is on the TV or t’internet, that doesn’t mean it’s a true record of events. Selective editing, angles, re-takes and so on all mean that we are being shown a version of the truth. But live TV – most people would surely assume that what you see is exactly what you get? Well, it’s not. And not only that but the camera is not just a recorder of events but a shaper of events; not a neutral, objective presence but a presence that is an active part of the very spectacle it purports only to record.

As part of a broader picture that sees 4 and 6 cards and thundersticks handed out to everyone, that sees the Cricketeers hyping up the schoolkids to sing and chant, that sees music played in the ground to get the crowd singing along, and the picking out of anyone in fancy dress on the big screens for everyone to cheer – we are encouraged to express our pleasure at the spectacle and our support of our side in a very particular way. It’s a way that feels distinctly at odds with how many people might want to enjoy it but it’s the only way the authorities appear to want us to enjoy it. It’s not a 90-minute football match, it’s an 8-hour cricket match: we really don’t need to pretend that every minute is action-packed, every spectator is out of their seat with excitement, do we?

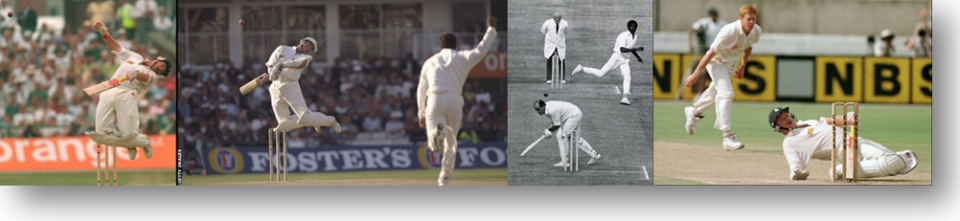

Without wanting to sound too curmudgeonly, I wonder if there is anything wrong with enjoying the game of cricket for what it is rather than feeling like you’re in a piece of performance art? In an era where scores of 300 are the norm and 400 is regularly within reach, and when so many truly thrilling players are showing spectacular skills, is this not enough? It feels as if cricket-the-product has become more important to the powers-that-be than cricket-the-game.

Went to the hockey double header on Sunday the most important fan interaction was after the game when the camera’s were off and parents, children and GB internationals played hockey together on the Lee Valley, you can’t fake sporting community and real engagement with fans

LikeLike

Agreed. That’s a very different experience and a positive, formative one for young fans.

LikeLike

I tend to agree with most of your piece Nick. I first encountered such ‘camera work’ whilst living in the States. During Baseball, Basketball, and American Football games, the ‘Kiss Cam’ was used during every break in play and still is. It seemed a novelty to me at first and gradually became annoying, probably because I had no one at the time to kiss! and maybe because I was usually surrounded by tobacco spitting all American males LOL

LikeLike

Thanks for that perspective Ian. As an aside, I truly hate the kiss-cam and sincerely hope it doesn’t make its way over here!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Don’t worry about sounding curmudgeonly, Nick, it’s the only way.

I dislike all the needless embellishments dreamt up by the ICC marketing people as much as most people (probably more), but I found that the atmosphere created by the Pakistan fans and the quality of the cricket yesterday helped them to fade into the background.

There were some interesting comparisons to be made with the Championship crowd I’d been part of at Arundel the day before, though.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Being there: reflections on being part of the crowd – Cricket Stuff